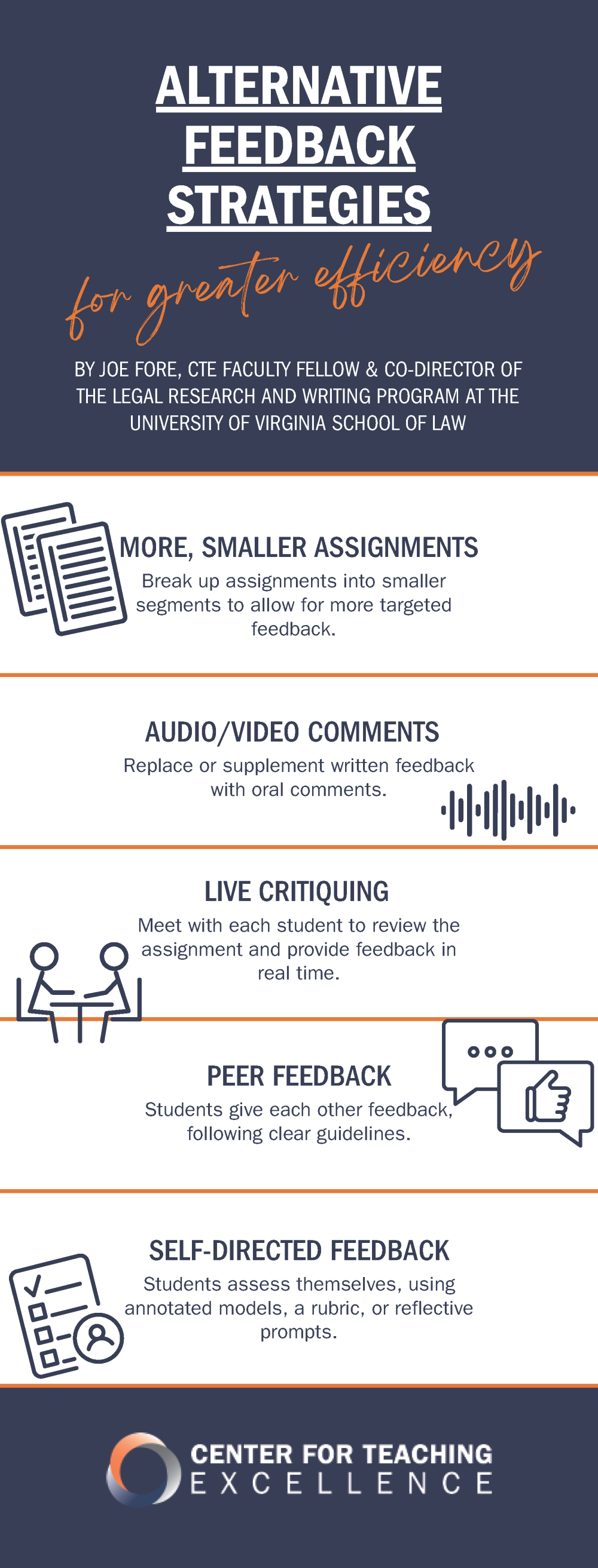

Alternative Feedback Strategies for Greater Efficiency

Consider different techniques that can lead to students getting more and better feedback overall.

Providing feedback on students’ writing is the single most valuable part of a writing-centric course. It’s also the most time-intensive part of teaching. So it’s understandable that many instructors balk at giving more feedback—the thought of sitting alone with a giant stack of papers, scribbling dozens of small notes on each one is just too much to take. But feedback doesn’t have to look like that. There are many ways to give effective feedback more efficiently. And when done correctly, these techniques can lead to students getting more and better feedback overall.

MORE, SHORTER ASSIGNMENTS

It can be tempting to procrastinate about giving feedback—to wait until those big, final papers or midterms come in to start commenting on them. But by waiting, you’re only making things worse—both for you and for your students. Now you’ve created one huge pile of papers that need grading at the same time, while some students are spinning their wheels or wondering if they’re on the right track. And without early intervention, the quality of their work might suffer—meaning that you’ll have even more to comment on when those papers eventually do come in.

One of the easiest and most effective ways to improve your feedback is to break up assignments into smaller segments. For example, rather than waiting until students write a full paper, you might have them turn in an abstract or a one-page summary of their thesis and then respond to that (Bean, 2011). Such developmental, forward-looking responses will give them some substantive help and ensure those final papers have sounder reasoning, which will reduce the amount of time spent commenting on papers on the back end.

Early comments are less cumbersome; you can focus on writing fewer, broader questions designed to prompt broad reflection by the student, rather than numerous, nitpicky sentence- or paragraph-level comments (Bean, 2011). And breaking up assignments into smaller chunks allows you to give more targeted feedback. Instead of waiting until the end and commenting on everything, you’ll be able to focus each round of feedback on more specific issues. Perhaps the first assignment focuses just on content, the next on organization, and then another round on stylistic issues. You can also introduce other very short tasks—such as a short journal entry, reflection, or in-class response—that reinforce key concepts or themes from the course (Bean, 2011).

Plus, adding smaller, more frequent assignments not only reduces your commenting burden; it’s also better for students. These low-stakes opportunities to try and to fail without fear of a devastating grade are critical for building students’ confidence and motivation—especially for those who may be unsure about their skills or their command of the material (Dark, 1999).

AUDIO/VIDEO COMMENTS

If you’re like me, it’s not so much thinking about the feedback that’s taxing—it’s writing it out that takes so much time and mental energy (not to mention the hand/finger cramps). One option for increasing efficiency is to replace or supplement written feedback with oral comments—either audio or video. As I wrote in my last CTE blog post, video feedback, in particular, offers advantages over written comments from the student’s perspective:

Research on video feedback suggests that the combination of audio and visual elements helps students understand and implement feedback. Research also suggests that video feedback increases student engagement, with students spending more time reviewing video feedback than written comments. And, specifically, from a tone perspective, seeing and hearing the instructor leads students to see video feedback as authentic, personal, friendly, and positive. (Bahula & Kay, pp. 6537-6538)

I’ve used a hybrid technique to deliver feedback this year—blending video and written comments. I review students’ writing and make some written comments for smaller issues: grammar miscues, stylistic tips, specific organizational or substantive points. But for larger or systemic, or harder-to-fix issues, I simply flag them with a quick note. Then, I record a short Zoom video, where I talk to the student while sharing a screen that shows their paper. In these videos, I can provide holistic comments and explore the flagged issues in more detail. This strategy relieves me of the pressure of coming up with long, detailed written explanations of complex issues; instead, I can talk it out. This saves time and potential confusion, since I can usually articulate the issues more clearly orally than I can in writing.

“LIVE” CRITIQUING

Another time-saving technique—one widely used in law-school writing courses, where large class sizes and complex assignments are common—is “live grading” or “live critiquing.” The idea is simple: the instructor and student meet, and the instructor reviews the paper and provides feedback in real time (hence, the “live”) (Montana, 2019). (I recommend this one-hour, virtual panel on the pedagogy of live commenting—sponsored by Stetson Law School.)

When using this technique in the past, I’ve found it helpful to read the paper out loud a paragraph at a time, highlighting things I want to discuss or making small notes (Hemingway & Smith, 2016; Montana, 2019). Then, after that paragraph, I’ll look up and talk to the student about what I’m seeing. (While a key aspect is responding to the papers “live,” most writing professors skim the papers ahead of time so they know some key issues they want to raise during the conference.)

For the instructor, live critiquing provides substantial efficiency gains. Collapsing the initial reading, feedback, and student conference into a single meeting puts a hard limit on the amount of time spent on any one student paper. (This is especially important for those of you who, like me, set a goal that you’re only going to spend X number of minutes commenting on each paper—only to look up after finishing the first paper and realize you’ve spent twice as long.)

Live critiquing also offers pedagogical benefits. By limiting our feedback window, we constrain how much we can say on each paper and, in turn, avoid overwhelming students. Instead, we can focus our comments on the most critical issues. Another benefit is that students get to see how a reader would react in real time—just like the real world—not how a reader responds after digesting the entire piece, thinking about its issues, then writing carefully thought-out responses. Students get to see exactly where the reader gets tripped-up, frustrated, or confused—as it’s happening.

The live aspect of the reading also has tremendous interpersonal benefits. While it can seem intimidating, giving face-to-face comments allows you to avoid tone issues that might crop up in written comments. You can adjust your feedback on the fly, modifying your tone based on how a student reacts to initial remarks. And, of course, a final benefit is that both you and the student can seek immediate clarification. Rather than wasting time guessing what a student might have meant and writing a comment on it, ask the student what they were trying to accomplish in a given paragraph or sentence. And students, too, can immediately follow up if they don’t understand a particular piece of feedback (Montana, 2019).

PEER FEEDBACK

Another tip for reducing your commenting load: let someone else do the work. One possibility is to let students give each other feedback (Bean, 2011). It might seem daunting to let students help teach one another. You may think students are: (1) too nervous about letting anyone else look at their work; or (2) not qualified to provide feedback. But I’ve consistently been surprised by my students’ ability to give candid and thoughtful feedback to their classmates—and their ability to accept feedback in a collaborative and good-natured way.

Plus, it’s not only receiving feedback that’s valuable for students’ learning; giving feedback also reinforces valuable lessons. “Requiring students to articulate what does and doesn’t work in a piece of writing forces them to identify writing and analytical problems with precision and increases the likelihood that they will be able to incorporate those lessons into their own writing” (Wilensky, 2020, pp. 70-71).

Of course, just like everything else in your course, peer feedback activities must be designed thoughtfully. Here are some tips:

Wait a while. Because giving and receiving feedback can be a bit awkward, it’s crucial that students already have some rapport with their classmates before attempting peer feedback—probably at least a month into the semester (Wilensky, 2020). Also, it’s best if you’ve already had them work in small groups or pairs to do other kinds of editing so that the peer editing component feels like a small extension of something they’re used to doing.

Frame the exercise. Before students comment on each other’s papers, explain the purpose and structure of the activity. With peer feedback, it’s critical to mention the pedagogical benefits of the exercise so that students know it’s a valuable learning activity—not one designed to make them feel uncomfortable. They’ll also be more invested—both in terms of the feedback they’ll give and in terms of what they’ll get from the experience.

Give clear instructions. Lastly, be sure to give very explicit instructions: time limits, what they should focus on (organization, content, style, etc.), and what you want them to do (highlight unclear portions, write comments, propose edits, etc.) (Wilensky, 2020). You can make the evaluator’s task more approachable by framing the job in terms of their reactions: “Rather than requiring an evaluation about the adequacy, effectiveness, clarity or logic of some aspect of the work, you can ask students to identify features or parts of the work, as each student sees them, or give their personal reactions to the work” (Nilson, 2016, p. 273). Remind students to look for things that could be improved and things their classmate did well. Identifying what their peers did well reinforces lessons you’ve taught and gives students attainable models that they can emulate in their writing.

SELF-DIRECTED FEEDBACK

One final idea is to give students more of a role in assessing themselves. While students often have trouble knowing where they need improvement (otherwise, they would have already done it), there are ways to help guide students to have more self-directed feedback.

Annotated models. One popular method for giving students ownership over their feedback is to provide “models” or “samples” of good work for them to emulate. By looking at good work, the theory holds, students will see where they fall short and fix it. But, as novices, students often have trouble deciphering precisely what is “good” about the “good” work you show them and how it relates to what they’re doing (Frost, 2016, p. 947).

So, for model answers to be useful for students, you need to annotate them, including in-depth explanations showing exactly what a particular model does well and why it’s important (Frost, 2016). And, ideally, you’ll provide more than one annotated model to prevent students from believing there’s only one “right” way to write effectively and hewing too closely to that model (Frost, 2016, p. 963). If that sounds like a lot of work, you’re right; it’s essentially the same as providing detailed comments on a student’s paper. Creating good annotated models takes a sizeable up-front time investment. But, if done well, annotated models can replace individualized comments on many student papers—and can even be used for semesters to come.

Global feedback. Another similar technique is to provide generalized feedback to the entire class—feedback that addresses common issues that many students are making. Again, this provides an efficiency gain: rather than writing the same comment on 20 different student papers, you can take a few minutes of class time to discuss the common issue, while leaving students to identify that their paper has that issue (Bean, 2011).

For example, in my courses, I sometimes start one week’s class by discussing some of the common shortcomings that I’ve seen in reviewing the previous week’s assignments. I’ll usually project a real example of a sentence or paragraph (anonymized, of course) onto the screen and then discuss the issue that I’ve been seeing. (In addition to making the examples anonymous, I’m always careful to reiterate that this is an issue that many people have so that no one thinks they’re being singled out.) I’ll usually follow that up by contrasting it with another actual student example (again, anonymous) that’s written in a clearer or more effective way.

Self-“grading” and self-reflection. One strategy for helping students assess their own writing is to put them in the shoes of the grader (Nilson, 2016). Give them a rubric—perhaps the one you use for grading assignments—and ask them to evaluate their papers specifically in those areas. The rubric would have to be very specific to walk them through what they should be looking for. And to keep from overwhelming students, it’s best to focus on one area at a time: overall organization, use of sources, paragraphing, etc.

Another technique is to have students do more holistic, reflective writing about their assignments. After looking at a model answer or self-“grading” with a rubric, you could ask students to identify common areas where they feel they are struggling or develop a plan for how they want to correct those issues (Kostange, 2016). Lastly, it can be valuable to have students assess their writing process, including the emotions they felt while writing. Some of your students’ writing difficulties might stem from failures of process or motivation—not failures of understanding. By identifying their flawed processes and feelings of frustration, students will be better positioned to identify and manage them in the future (Bishop, 2018).

References

Bahula, T., & Kay, R. (2020). Exploring student perceptions of video feedback: A review of the literature. ICERI2020 Proceedings, 6535-6544.

Bean, J.C. (2011). Engaging ideas: The professor’s guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom (2nded.). Jossey-Bass.

Bishop, K. (2018). Framing failure in the legal classroom: Techniques for encouraging growth and resilience. 70 Ark. L. Rev. https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/working_papers/2/

Dark, O. C. (1999). Principle 6: Good practice communicates high expectations. Journal of Legal Education, 49(3), 441-447. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42893611

Frost, E.R. (2016). Feedback distortion: The shortcomings of model answers as formative feedback. Journal of Legal Education, 65(4), 938-965.

Hemingway, A. & Smith, A. (2016). Best practices in legal education: How live critiquing and cooperative work lead to happy students and happy professors. Second Draft, 29(2), 7-9.

Kostange, R. (2016). Developing growth mindset through reflective writing. Journal of Student Success and Retention, 3(1). http://www.jossr.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/KostangeArticle-3.pdf

Montana, P. G. (2019). Live and learn: Live critiquing and student learning. Perspectives: Teaching Legal Research and Writing, 27(1), 22-27.

Nilson, L.B. (2016). Teaching at its best: A research-based resource for college instructors (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Shu, D., & Vukadin, K. T. (2019). Catching on: How post-critique assessments deepen understanding and improve legal writing. Second Draft, 32(2), 35-39.

Stetson University School of Law. (2021). The pedagogical method of live commenting grading. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3MNOnojuYpM

Wilensky, B. H. (2020). How I finally overcame my apprehension about peer review. The Second Draft, 33(2), 69-74.