Alternative Grading: Practices to Support Both Equity and Learning

How can instructors harness their grading practices to support equitable outcomes and deep learning for all students?

Grades are typically a poor representation of teaching and learning. For this reason, educational developers encourage instructors to focus on developing significant and robust learning objectives, meaningful and authentic assessments, and positive and compassionate relationships with students. Alternative grading schemes can support those efforts.

Reconsidering how and why we grade can help us develop practices that reduce students’ anxiety, address some of the inequities of traditional grading schemes, save us time, and foster more positive, meaningful communication between us and our students. We’ll share how alternative approaches can

1. help to address some of the problems with traditional grading,

2. introduce you to a grading method that can easily be adapted to your course, and

3. give you step-by-step instructions for designing your own alternative grading scheme.

What are the problems with traditional grading? Why should I consider alternatives?

Traditional approaches to grading create many problems. Grades dampen students’ innate curiosity and motivation to learn, and increase extrinsic motivation (Kohn, 2012; Chamberlain, Yasu, and Chiang, 2018; Michalides and Kirshner, 2005). They also adversely impact students’ mental health (Pulfrey, 2011), decrease their enjoyment of school and of learning, foster competition among students and adversarial interactions between students and instructors, reduce students’ interest in and attention to written feedback, and encourage students to avoid challenging tasks (Schinske and Tanner, 2014). Grades negatively affect instructors as well. The process of grading is time-consuming and tedious. It includes none of the elements that make teaching fun and rewarding, and the obligation to assign grades undermines the positive, supportive relationships that we hope to cultivate with students.

Traditional grades bear little relationship to learning. Receiving and integrating feedback is an essential part of the learning process, but because grades are retrospective, they serve as a poor feedback mechanism. The meaning of grades may also not be obvious to students; they do not understand what is expected of them in order to earn a particular grade, nor do they know what criteria to use to self-assess their progress. The relative opacity or transparency of grades is highly dependent upon instructors’ assessment practices, and alternative grading systems encourage greater transparency and better communication between students and instructors (Winkelmes, 2016).

Of all the problems with grades, perhaps the most egregious is that they reinforce historic and continuing inequities in higher education. Students from different demographic groups experience very different outcomes in terms of both grades and college completion rates, and these differences persist even when researchers control for prior preparation and academic ability (Molinaro 2019; Johnson, Molinaro, and Motika 2018; UC Davis CEE Equity Project). Thus, grades are more likely to reflect students’ demographics, access to technology, access to academic support resources, financial constraints, and mental and physical health than their actual learning in a given course or semester. For these reasons, grades cannot be trusted as accurate measures of student achievement. And if we care about rectifying educational inequities, then we must interrogate and alter our grading practices.

Alternative grading schemes invite us to reconsider not only how, but also why we grade. They invite us to embrace the philosophy that higher education should function as a universal public good, rather than as a private, market good that evaluates and sorts students for the purposes of career preparation. As Stuart Tannock asserts, “The question of grading in assessment is just one piece of thinking through what a genuinely empowering, emancipatory, and democratic model of public higher education should look like” (2017, p. 1346). Our traditional grading system encourages students to adopt a consumer mentality toward education, in which the point of college is to receive grades on the way toward a degree, rather than to learn. If education ideally fosters “critical, reflexive, independent and democratically-minded thinkers” (p. 1349), then grading as commonly practiced stands in the way of that goal.

At their most radical, alternative systems do away with grades entirely in favor of holistic and continuous forms of assessment and feedback. In most cases, individual instructors cannot decide unilaterally to abolish grades, but they can transform the process by which students’ grades are determined. Alternative approaches include pass/fail or mastery-based systems, narrative or portfolio-based grading, and dialogic/participatory forms of assessment such as contract grading. Many alternative approaches invite students to exercise the complex skill of thinking critically about their own learning and their goals for their education. Non-traditional grading practices offer an “opportunity for students to deliberate cooperatively on the terms of their experience, to develop democratic agency... Democratic deliberation in classrooms is counter-hegemonic, against the dominant market forces directing society" (Shor, 2009, p. 17). Although the details of each grading approach differ, the goals are the same: to reduce or eliminate hierarchies between students and instructors; to reclaim the expansive, democratic, and liberatory purposes of higher education; and to transform grades into more accurate reflections of student learning.

One alternative grading approach is called specifications grading, aka specs grading, which integrates components of various alternative grading systems. When done well, it encourages students to prioritize learning over grades and invites them to participate in the process of determining what counts as acceptable evidence of learning. Although no studies exist yet that definitively show specs grading to be more equitable than traditional methods, we believe it has the potential to serve the goal of equity if it is implemented carefully, intentionally, and with a deep understanding of how institutional racism operates in grading. Below, we’ll tell you more about specs grading and how it works, and then walk you through the process of developing your own specs grading system.

What is specifications grading?

Specifications grading is an alternative approach to grading that prioritizes transparency, student mastery of learning objectives, careful alignment between assessments and learning objectives, and process and growth-oriented approaches to learning. Though students ultimately earn a letter grade for the course, the method of assigning that grade differs from the traditional method of calculating a weighted average of all individual assignment grades. In specifications grading, instructors set clear, comprehensive expectations for successful completion of each assignment (i.e., an assignment’s specifications, also called expectations or criteria). Instructors then bundle together assignments to create pathways to each grade level. The grade-level bundles are differentiated by the quantity of assignments, the difficulty and complexity of the work, or both.

The final course grade is determined by students meeting specifications for all assignments in a particular grade bundle. Individual assignments do not receive letter grades; each assignment gets credit only when it meets all of the specifications. This binary evaluation system is an essential component of specifications grading; instead of attempting to parse fine gradations in quality of student work, an instructor sets the expectations for each assignment to a level that indicates an acceptable amount of learning. The definition of “acceptable” for each assignment should be closely tied to the relevant learning objectives for the assignment. In order to lower the stakes of any given assignment, specifications grading systems generally allow for (limited) revision opportunities, and instructors provide process-oriented feedback on each assignment, so that assignments that do not yet meet all specifications may be improved.

Specifications grading systems reconcile the tension that instructors may feel between maintaining rigorous standards for learning and treating students with empathy and understanding. Well-designed systems articulate high but not impossible expectations for students’ learning. Each assignment’s specs should define what solid, high-quality, though not perfect learning looks like (a common benchmark we recommend to instructors is to describe in detail their mental image of B or B+-level work). Because all assignments’ specs are binary, and do not vary based on the grade bundle students complete, instructors who use specs grading ensure that all students meet rigorous standards for learning, even those students who complete the C or D grade bundles.

At the same time that specs grading ensures high-quality learning, it also allows instructors to attend more fully to students’ well-being. Specs grading requires total transparency, which significantly decreases the anxiety students feel about grades, while also increasing their sense of confidence and sense of belonging in the classroom (Winkelmes, 2016). When specs grading is done well, instructors communicate all evaluation criteria for student learning at the start of the semester, provide examples of student work that meets expectations, and regularly have conversations with their students to gauge their understanding. Additionally, we encourage instructors to invite students to contribute to the process of defining specifications for particular course elements, such as class participation. Through engaging in this ongoing process of developing mutual understanding, specs grading restores equity to grading and allows students to take ownership of the evaluation process. Grades are no longer based on assumptions that may be invisible to some students but intuited by others.

Designing a specifications grading system

The possibilities for specifications grading schemes are limitless and shaped by a course’s unique learning objectives, format, assignments, content, student characteristics, learning technologies, and teaching and grading supports. This allows you to create a system to best support your learning environment, but the high degree of choice can sometimes feel overwhelming. To get you started, we’ve outlined eight steps to help you create an equitable, transparent specs grading system that fosters learning and engagement and encourages students to produce high-quality work on their first try.

1. Determine your learning objectives.

As with any course design activity, you’ll begin by carefully considering your course-level learning objectives. What is it that you want your student to know, be able to do, or value by the end of your course? Your learning objectives should be concrete and measurable. While the number of learning objectives typically falls in the 4-8 range, you might consider scaling back in a specs grading system to those you deem essential. In addition to ensuring your focus remains on the most important aspects of your course, this will remind you to keep things simple (see #8).

2. Determine your assignment bundles.

Once you’ve settled on a small, robust set of learning objectives, you’ll create bundles of assignments to measure your objectives. One bundle might include, for example, daily or weekly quizzes, another might include extended assignments, blog posts, or problem sets, and others might include essays, hour exams, or projects.

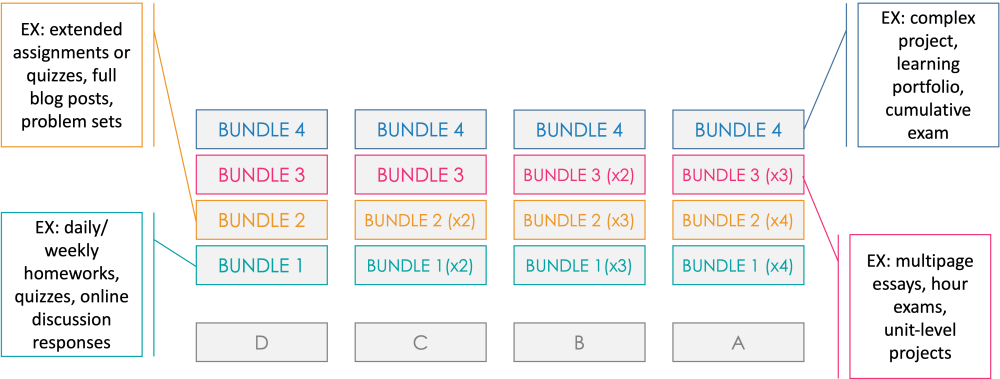

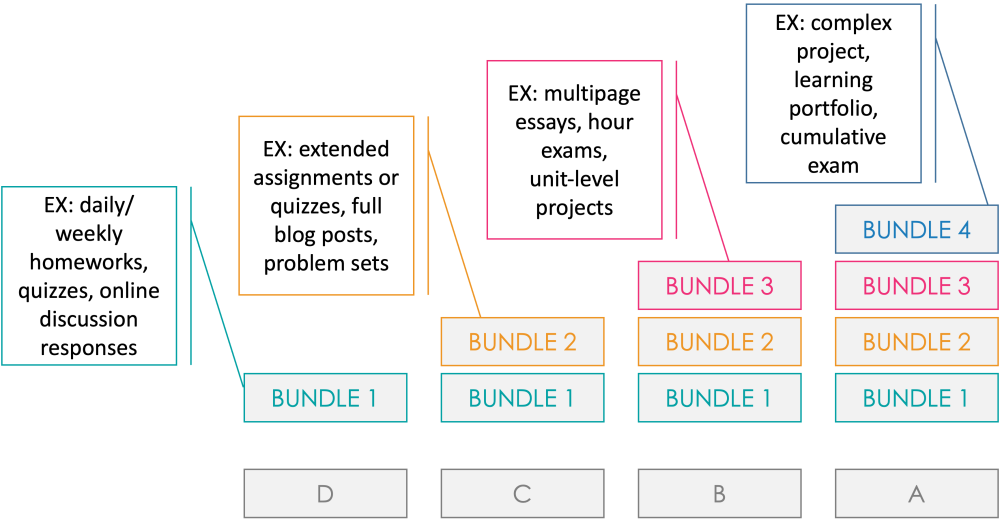

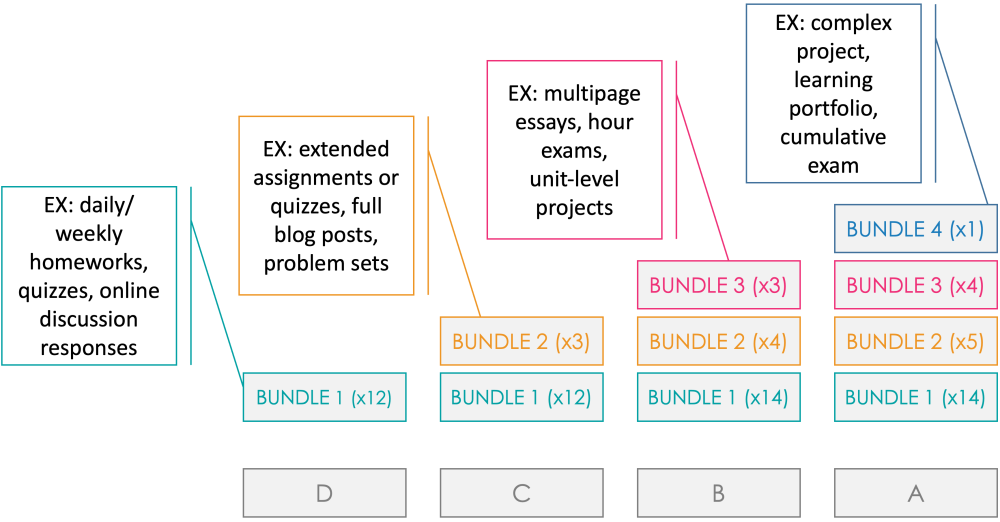

There are several ways to organize your bundles. Three of the most common options are shown in Schemes 1-3. They differ by the emphasis placed on the learning objectives and the quantity of work.

Regardless of the bundling scheme you adopt, the lower-level bundles (BUNDLES 1 & 2) are often comprised of short, lower-stakes but regularly recurring assignments, such as weekly reading quizzes. This ensures that all students stay engaged throughout the course and achieve a minimum level of competency, proficiency, or mastery. Higher-level bundles (BUNDLES 3 & 4) include longer, more complex, or more nuanced assignments, or require students to meet specs on more of each assignment type. Using Scheme 3 to illustrate this point, C-level work might require students to meet specs on three BUNDLE 2 assignments, while B-level and A-level work might require students to meet specs on four and five BUNDLE 2 assignments, respectively.

It's important to remember that students aren’t eligible for higher grades unless they complete all the lower bundles to specifications. A consequence of this limitation is that students are not able to accumulate random points to get the grade they’ve come to expect. They must do all the work, at high quality, to earn the grade they choose to work toward. In other words, a well-designed specs grading scheme makes it difficult for students to do anything but the hard work of learning.

3. Articulate B-level specs for all assignments.

For each different type of assignment in your bundles, you’ll need to clearly articulate the purpose, task(s), and criteria. The criteria, or specs, are presented to students as a one-dimensional, holistic rubric that describes B or B+ work. There is no need to describe other rubric levels. Student work will either match or exceed the specs or fall short.

When describing the specs, you’ll want to be as concrete, detailed, and specific as possible, maybe even more so than you’ve been in the past. Depending on the assignment, good specs might articulate page or word counts, due dates, use of evidence, depth of argument, accuracy, precision, creativity, risk-taking, grammar, or mechanics. Remember to clearly define ambiguous terms, such as critical reflection, so that all students have a common understanding of what’s expected of them. Finally, it’s essential to frame the specs in terms of what success looks like.

4. Create annotated exemplars.

One of the biggest challenges with specs grading schemes is helping students understand the specifications. Rubrics only help so much. Students benefit from examples, especially when annotated. When you’ve taught the course before, it’s easy enough to get permission to share work from former students who met equivalent specs. Simply add marginal comments describing what the students did well and how those things reflect the specs. Don’t choose the best student work to share; pick one or two examples that show different ways to meet specs. Since by design the specs are concrete, detailed, specific, and framed in terms of what success looks like, there is no need to show examples that don’t meet specs. (If you’ve not taught the course before, it’s fair enough to share good examples after the first assignment. In this situation, you might consider allowing students a free token to revise and resubmit; see #6.)

In case you're curious, research shows that providing exemplars doesn't diminish originality or creativity or lead to plagiarism. On the contrary, studies show that at worst exemplars increase students' understanding of the assignment. Quite often, the quality of their work also improves (Dixon, Hawe, & Hamilton, 2019; Hendry, White, & Herbert, 2016).

5. Determine feedback mechanism.

For every assignment, you’ll determine whether a student "meets specs" or "does not yet meet specs." The "yet" in the latter emphasizes the learning-focused and growth-minded aspects of specs grading schemes. It implies that with feedback and additional practice students will eventually meet specifications. How quickly students do this will depend somewhat on receiving timely, quality feedback from you, a co-instructor, or a teaching assistant, particularly the first time they encounter an assignment type. Regardless of whether specs are met, you should provide improvement-focused feedback to all your students. What could they do more or less of in order to meet specs? Ideally, the feedback is framed as opportunities to improve clarity or accuracy, strengthen arguments, better demonstrate types of thinking, and so on.

Interestingly, you’ll spend considerably more time providing feedback at the start of a term in a specs grading system. Later in the semester, once students learn what they must do to meet specs, you’ll spend most of your time helping students see other possibilities or asking them questions that intrigue you. Because of the upfront costs, however, some instructors rely on alternative ways to provide feedback, such as audio or video recorded feedback, or use learning technologies such as iRubric or Gradescope.

6. Determine a token system.

Because grades are tied to completed bundles, it’s necessary to create a system that allows students a limited number of redos. The redos might be in the form of a revise and resubmit, a time extension, a dropped assignment, or an excused absence. Tokens—some prefer the language of tickets—help you and your students track this.

The tokens are a type of gaming economy. Students quickly learn the economy and try to use it to their advantage. Your job is to ensure the tokens are valuable and the economy advances one of two things: student engagement or learning. One way to increase value is to increase scarcity. Limiting the tokens, typically to three to four per student, forces students to make choices. Should they spend one early in the semester on a time extension for a C-bundle assignment or later in the semester on a revise and resubmit for a B-bundle assignment? One way to advance engagement and learning is to decrease the cost associated with things like revise and resubmit—maybe this costs 1 token—while increasing the cost of things like dropping an assignment—maybe this costs two tokens. You can also grant additional tokens for extra learning. For example, maybe students can earn one token for designing and leading a class discussion. Be stingy though or students will game the economy to the point where they can circumvent the overall specs grading system. (It’s important that students are not able to trade tokens with each other. Their only transactional partner is you.)

Regardless of the details, it’s essential that your token economy be equitable. Every student must have the same opportunities to use and earn tokens. For example, if you decide students can use a token to make up for an unexcused absence, then any student should be able to do so without providing an excuse. If a student’s absence is excused, say for a university-sanctioned event, this shouldn’t require a token. Alternatively, if you decide to grant a token for students attending 3-4 office hours before mid-term, you need to provide ways all students can earn this token, including remote options.

7. Create a robust “communications and marketing” plan.

Although gaining in popularity, specs grading schemes are foreign to most students. You’ll need to spend time describing your system and its nuances in the syllabus, on the course website, and in class. You might even want to hold group office hours just to talk through the system and work through cases. In each venue, clearly describe how your system works and why it benefits student learning. Emphasize that it increases transparency and equity, focuses everyone’s attention on learning rather than grades, and provides ways to recover when specs aren’t initially met. Remind students also that your specs grading system provides them a level of choice routinely absent in other courses. They can choose which assignments and bundles to complete, when to use tokens, and when to work for additional tokens. You can emphasize this point if before every assignment you remind students that the assignment is optional but required for a particular bundle.

Finally, it’s a good idea to periodically compare your “grade” notes with students’ to ensure each of you has accurately recorded assignments and tokens. Given there are no assignment grades, students can easily determine their progress toward a grade at any point during the term.

8. Keep it simple.

Because of the number of variables and variations, specs grading systems can get complicated fast. More often than not, complexity correlates with confusion and ultimately stress. You and your students will be happiest with a simple system. Focus on a small set of learning objectives; use as few bundles and assignment types as necessary; find efficient ways to provide the most useful feedback given the constraints of your course; offer a limited number of tokens and restrict their use to a few learning-focused things; provide multiple ways to communicate your system.

Examples

The following examples demonstrate variation in specs grading schemes and differing approaches to introducing the schemes in the syllabus.

Example 1: ENGL 2507: Identity, Selfhood, and Otherness in Renaissance Drama

This specs grading system emphasizes writing and regular engagement through pre-class discussion board and annotation posts (see specs for podcast assignment). Unique elements include:

One free essay revision opportunity.

Choice between multiple pathways to complete homework assignments (mix and match discussion boards, annotations, and live performances).

Plus and minus final letter grades determined based on participation (i.e., participation can boost a student's grade at any grade level).

Example 2: USEM 1570: Falling from Infinity

This specs grading scheme emphasizes the importance of participation (bundle 1) and class preparation (bundle 2). More complex learning objectives are assessed primarily through bundles 3 and 4 (see specs for digital story project). Unique elements include:

Some free revise and resubmit opportunities.

Token limits on some assignment types.

Ability to earn additional tokens by completing "extension" activities, e.g., summarizing or leading a class discussion.

Example 3: LASE 2559: Living Your Best College Life

The specs grading scheme emphasizes sustained engagement and personal growth through pre-class preparation activities (bundle 1), post-class reflections (bundle 2), and continuous development and revision assignments (bundle 3 & 4). Unique elements include:

Accommodation of A-F and CR/GC/NC grading systems.

Token (aka ticket) system that accounts for dependencies (e.g., if a student drops a pre-class assignment, they also have to drop the post-class reflection since these are dependent).

N.B. You may notice that the examples offered here use "bundles'" differently. In the first example, a bundle refers to the collection of assignments required to earn a particular grade. The second example has multiple assessment types under each bundle. In the final example, each assignment type is a unique bundle. Either use of the term is acceptable as long as it's used consistently within your course.

Resources

If you’re interested in learning more about alternative grading schemes or want to discuss your own specs grading system, schedule a one-on-one consultation with a CTE faculty member.

This Google Folder contains sample specifications grading assignments and schemes (also shared in the Examples section above).

Meaningful, Moral, and Manageable? The Grading Holy Grail - In this post, an instructor shares why she decided to try specifications grading and lessons learned from her experiment.

Teaching More by Grading Less (or Differently) - After reviewing the history of and research on grading practices, the authors share four strategies for making the process "more productive, better aligned with student learning, and less burdensome for faculty and students."

References

Chamberlin, K., Yasué, M., & Chiang, I-C. A. (2018). The impact of grades on student motivation. Active Learning in Higher Education, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787418819728

Dixon, H., Hawe, E., & Hamilton, R. (2019). The case for using exemplars to develop academic self-efficacy. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(3), 460-471.

Feldman, J. (2019). Beyond standards-based grading: Why equity must be part of grading reform. Phi Delta Kappa, 100(8), 52–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721719846890

Johnson, T., Molinaro, M., Motika, M. (2018, November). Exploring Factors in Course Grade Equity (and what we might do about it). California Association for Institutional Research, Anaheim CA.

Hendry, G. D., White, P., & Herbert, C. (2016). Providing exemplar-based ‘feedforward’ before an assessment: The role of teacher explanation. Active Learning in Higher Education, 17(2), 99-109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787416637479

Kohn, A. (2012). The Case Against Grades. Education Digest, 77(5), 8–16.

Michaelides, M., & Kirshner, B. (2005). Graduate Student Attitudes toward Grading Systems. College Quarterly, 8(4). https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ848740

Molinaro, M. (December, 2019). Institutional Infrastructure for Teaching and Learning Data. An invited talk for the University of Virginia leadership. December 13, 2019

Schinske, J., & Tanner, K. (2014). Teaching More by Grading Less (or Differently). CBE—Life Sciences Education, 13(2), 159–166. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.cbe-14-03-0054

Tannock, S. (2017). No grades in higher education now! Revisiting the place of graded assessment in the reimagination of the public university. Studies in Higher Education, 42(8), 1345–1357. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1092131

Winkelmes, M.-A., Bernacki, M., Butler, J., Zochowski, M., Golanics, J., & Harris Weavil, K. (2016). A Teaching Intervention that Increases Underserved College Students’ Success. Peer Review, 18(1–2). https://www.aacu.org/peerreview/2016/winter-spring/Winkelmes